|

Return to Echo Mtn. Echoes, Spring 1999 Cover

Mount Lowe Power

By John Harrigan

Introduction and Incline Machinery When I first started looking into the power systems for the Mt. Lowe Railway, I knew that there were pre-1906 and post 1906 designs. I had looked at the pictures in the various books but I had not paid a great deal of attention to what I was look at or reading about until I started the research.The earliest description of the design for the lift mechanism comes from April of 1893. Initially, the motive power was supplied by a 75-horse power Keith, 500 volt DC motor that turned at about 800 rpm.

|

There were several safety items that incorporated on the main drive machinery that are of note. Attached to the first intermediate gear shaft was a belt going to a fly-ball regulator mounted on the ceiling. As the shaft turned, the weighted balls would move or "fly" out. If the gears turned too fast, the fly balls would move out past a preset position and the fly-ball regulator would apply the large emergency brake above the main grip wheel. The operating point for this emergency brake could be adjusted or reset by the operator in the operator’s room upstairs. Later designs also incorporated an electric circuit breaker in this system that would shut down the drive motor along with applying the brake in the event of an over-speed condition. The main brake was also located on the first intermediate gear shaft. The operator would manually engage or release the brake from his operating area by moving a large lever.

|

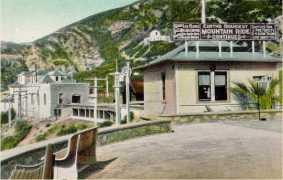

| This is how the powerhouse looked before the fire of December 9, 1905 as depicted on a postcard from the time. |

The operator in the incline powerhouse had to know when the passengers at the bottom were safely on or off the incline car and when to start the cars in motion. Likewise, the conductors on the incline cars had to know when the operator was going to move the cars. The conductors on the incline cars had a "magic wand" that they could touch to a telegraph type wire that ran along each side of the incline and signal the operator when to start and stop the cars from any point on the incline. The wand was a wooden pole with a copper wire tip and an insulated wire that ran from the tip to the metal axle on the incline car. By touching the wand to the wire, the conductor at the bottom of the incline would complete a circuit through the rails and ring an electric bell at the top and bottom of the incline. The conductor at the top of the incline would use a hand signal to the incline operator when he was ready to move. The incline operator would then acknowledge the signals from both conductors with another signal on the bell before he put the incline cars in motion.

|

| In the background of this Incline souvenir photo you can make out the new Powerhouse under construction in 1907. |

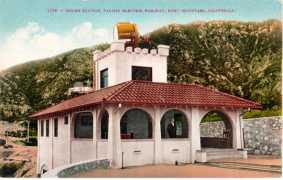

The wooden control house was destroyed in a windstorm and fire of December 9, 1905. Temporary service was restored to Echo Mountain from the Altadena Substation on January 3, 1906. A temporary operator’s room was constructed to allow operation during the construction of the new Incline Powerhouse. The new Incline control House was completed in 1907 and the machinery was cleaned up, refurbished and a new motor installed. The new motor was rated at 100 horsepower that turned at 500 rpm. This change lowered the speed of the grip wheel to 13 rpm and increased the time of the trip from Rubio Canyon to approximately 8 minutes and dropped the speed of the trip to 4 miles per hour. The operators control room in the new incline powerhouse was located on the second floor of the new building, giving the operator a better view of the positioning of the cars at the top of the incline. This arrangement remained the same until the end of the railway.

The Power System

Conceptual Design

The earliest description of the power system said it was to incorporate three water driven generators and 300 storage batteries. According to the Electrical Engineer, Almarian William Decker, the incline system would require only 15-horse power to raise the empty car, but 45-horse power to raise a full car. If a full car were descending with an empty car coming up, then the system would return 15-horse power back to the batteries. Likewise, the trolley cars traveling from Rubio Canyon down to Mountain Junction in Altadena would not consume power, but would generate power as they traveled down hill. Decker estimated that the system would regenerate about 40 percent of the power consumed on the trip from Mountain Junction to Rubio Canyon. |

| This is how the newly completed powerhouse looked in 1907. Take note of the Searchlight now in its final resting place atop the powerhouse. |

The remaining power loss would be made up by a series of water driven power plants in Rubio Canyon and above. These generators would be spaced at elevations about 1400 feet apart. This would have placed them in Rubio Canyon, Echo Mountain, and either somewhere around Crystal Springs and the site of the Alpine Tavern or down at Mountain Junction.

Decker calculated that the total power requirements for the system would be met in only two hours of operation each day leaving 22 hours to recharge the batteries. Without water, or because of other problems, the batteries would be able to handle the power requirements for one day, but would then require a full 24 hours for complete recharging. The two-hour time frame was based on the railway only going as far as Echo Mountain since it takes 25 minutes to go from Mountain Junction to Rubio Canyon, and another 6 minutes to travel up the incline to Echo Mountain. Four trips per day would yield 2 hours and 4 minutes of operation per day.

Based on all of this information, I have calculated that a battery system rated at 40 Amp-Hours minimum would supply the power for the system. The cells of that day were rated at 2 volts each, so the total battery capacity would have been 600 volts DC. Using standard design practices for the day, the batteries could have been recharged in 8 hours under normal use and would have required a generator capacity of only 3000 watts, or 4-horse power. This would have been reasonable for the water supply available in Rubio Canyon. Even if a 120 AH battery was used, the hydro generation system would have been capable of driving it. The problem was the availability of water.

Late 1893 to Early 1894

The hydro-generators in Rubio Canyon did not supply power to the railway for the first nine months of operation. A "temporary" power plant was built at Mountain Junction in Altadena. The Altadena power plant started out with one 50-horsepower Otto engine and a 50-horsepower Edison bi-polar generator. This engine and generator provided all of the power for the opening. After opening day, a second 50-hp Otto engine was added along with a 150-hp generator. The Otto engines have been rated as high as 60 hp each and were said to be able to produce 150-hp when belted together on the countershaft. To assist in starting the large engines, a 10-hp Otto engine was installed in the power plant. The Otto engines were designed to operate on illumination gas, distillate, and gasoline. Inexpensive gasoline was in ready supply so it was the primary source for fuel for the engines. The Professor supplied gas to the top of Echo Mountain from his "gas" plant in Pasadena and as a backup to the gasoline at the Altadena power plant. The "temporary" Altadena power plant was the main source of power during the dry months for many years.

|

| This is an early advertisement for another of Lowe's ventures the Pacific-Lowe Gas and Electric Works. |

By early 1894, there were two hydro-plants installed on the system at Rubio Canyon below the pavilion and further down the hill at Cabrillo Heights.

The Rubio Canyon power plant initially had three generators and turbines. Two were rated at 50 hp and one at 30 hp. No pictures or other evidence have been found of all this equipment in service at the same time. The connection and arrangement of this facility seemed to change on a monthly basis. The water from this power plant was directed to a reservoir across Rubio Canyon and was then piped down hill to the Cabrillo Heights power plant.

The Cabrillo Heights power plant equipment was rated at 50 hp. There are no records that give the exact location of the Cabrillo Heights power plant, or how long it remained in service. Cabrillo Heights was located a short distance down canyon at an elevation 450 feet below the Rubio Canyon Power Plant. Based on Topo map elevations, it was most likely down Rubio wash in the area between what are now Rubio Canyon Drive and the end of Holliston Avenue.

1894 to 1895

|

| Water from high up in Rubio Canyon was connected by 8" pipe to a 44" turbine wheel which drove a 100-hp generator. |

At this time, there was one 19-inch turbine wheel belted to two different generators. The generators were turning at different speeds, which would produce different voltages, most likely, 500 volts for the trolley and Incline motors, and 110 volts for the searchlight and incandescent lighting. Sometime during 1894, an eight-inch water line was installed from a small man-made lake in the canyons above the Rubio Pavilion at a place just above Grand Chasm Falls at an elevation 287 feet higher than the generators in Rubio Canyon. The water from the eight-inch line was connected to a 44-inch turbine wheel, which drove a 100-hp generator. There were also two of the smaller generators arranged to provide backup power for the trolleys and incline and 110 volts for lighting off the same turbine. The 19-inch turbines do not appear to have been service at this time.

Based on the calculations of a mechanical engineer, the small water line from Echo Mountain was capable of producing less than 25 hp, which was adequate for Decker’s original design. The larger 8-inch water line was capable of producing at least 125-hp. This was more than enough to drive the 100-hp generator and at least one of the smaller generators for lighting but at full output it would have consumed over 3700 gallons per minute. Its use was limited to high flow times of the year and to starting the gas engines at the Altadena and Echo Mt. Power Plants.

|

| 1893 Worlds Fair Searchlight reflecting the image of the Echo Mt. House was run by small DC generators in Rubio Canyon when water was available. |

During this time period, Alternating Current or AC, made its first appearance on Echo Mountain. In August of 1894, the great searchlight first arrived on Echo Mountain and was energized at half-power by hydropower or DC on September 10, 1894. The Echo Mountain House opened on November 24, 1894. Power for the searchlight and the Echo Mountain House lighting was supplied from one of the small DC generators in Rubio Canyon, when water was available, or by the Altadena power plant 1100 volt AC circuit after it was transformed down to 110 volts AC on Echo Mountain. 1100 volt AC power most likely came from the Altadena Power Plant. Since the trolley system was operated during the day, and the lighting was used at night, it is reasonable to assume that the engines would drive the trolley generators during the day and the lighting generators at night. Because gas lighting was available at the Echo Mountain House, the electrical generators could have been shut down late at night to save gas and ware and tear on the engines. One of the interesting notes on the AC power system is that only one conductor was run from Altadena. The return conductor for the current was the trolley rail, which also served as the return conductor for the trolleys 500-DC. This could create some very interesting and dangerous conditions if there were any loose connections in the rails, or if the wiring systems got crossed. Passing the alternating current through the iron rails would cause the rails to heat when high currents were passed, like when the searchlight was on. This type of operation would further bolster the case for furnishing AC and DC at different times, and the railway generating its own AC.

|

| 1895 powerplant |

In 1895, a power plant was built on Echo Mountain. This power plant

had a 75 and 35-hp Edison Bi-polar generators and two 60-hp Otto engines. Gas for the

engines and the gas lighting in the Echo Mountain House was piped from the

professors’ gas manufacturing plant eight miles away in Pasadena and stored in a

large gas storage tank constructed next to the power plant. Energy from this plant was to

power the Alpine Division of the railway and the incline machinery. The Echo Mountain

power plant appears to be much simpler than the Altadena plant in its layout and

operation.

1896 and 1897

Because of the financial problems Professor Lowe was having, and the foreclosure proceedings in court, there were no major changes found to the power systems during this time period. 1898 There were two major changes of note in 1898. The first was that a second conductor was added to the 1100 volt AC system from Altadena to the end of the circuit. The second was that the P&MW Railway contracted with the Southern California Power Company to furnish power to the railway. The Edison Electric Company of Los Angeles purchased the Southern California Power Company in June of 1898. The power for the P & MW was generated at the Santa Ana Canyon No. 1 and transmitted some 90 miles over a 33,000 volt 3-phase, 50 cycle AC transmission line to Substation No. 1 at Second and Boylston in Los Angeles. From there it transmitted to Pasadena and the Altadena Power Plant. At that time, this was the longest transmission line of that voltage in the country. The original Altadena power plant continued to furnish some power until it was replaced in 1905 by the new Altadena substation. 1899 to 1905In April of 1899, the P&MW became the Pasadena and Mount Lowe (P&ML) Railway. A new 300 kW Rotary converter was installed at the Altadena power plant energized on July 1, 1899. During this same time, a new powerhouse was built on Echo Mountain just East of the original powerhouse. A new motor-generator unit was installed to convert 2200 volts AC to 600 volts DC for the trolley system. The foundations for the 1899 Power Plant on Echo Mountain indicate that two motor-generator sets were ultimately installed. These units were used to supply power for the incline machinery and for the Alpine Division trolleys. The Hydro-generators in Rubio Canyon continued to act in a backup capacity during this period of time.

The P & ML railway was purchased by Henry E. Huntington on June 1, 1900 and was incorporated into the Pacific Electric Railway on November 10, 1901. During this same time period, the Rubio Canyon power plant and equipment was probably removed because of flooding. The addition of the improved power source on Echo Mountain eliminated the need for the Rubio Canyon machinery. Besides flooding the machinery and dining area, the rush of water through the canyon in the winter caused considerable damage to the stairways and piping and necessitated continual maintenance.

|

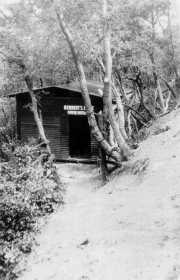

| Another power house used further up past Alpine Tavern was

Herbert's Powerhouse. Herbert was the source of power for the OM & M RR. Photo courtesy Vic McVey. |

Pacific Electric built the Altadena Substation in 1905 next to the original powerhouse, and demolished the old power plant once the new substation was put into service. The new power plant contained the 300kW Rotary converter and several large motor-generator units. The old Otto engines served for another 30 years operating irrigation plants in Fullerton and San Diego, California.

The fire of December 9, 1905 destroyed the power plants on Echo

Mountain along with all of the other buildings on Echo Mt. except the Observatory.

1906 to 1938

|

| Rubio Canyon reservoir |

There is not much in Rubio Canyon today. There are still a few foundations that the winter waters have not destroyed yet, but unless you know what you are looking for, you may miss it completely. The old reservoir used to impound the water for the Cabrillo Heights Power Plant can be seen across the canyon from the right-of-way just below the location of the Rubio Pavilion.

On Echo Mt., the foundations of most buildings are still there. The original Incline Powerhouse was replaced with the new one in 1907 and destroyed by the Forest Service in 1962. The wall where the cables exited the basement is from the original structure. Most of the building and machinery foundations are still in place for the 1895 and 1899 Power Plants. On the lower level just West of the 1895 Power Plant are the support members for the gas tank.

Little remains of the Mt. Lowe Railway except the memories and dreams in the minds of those who come to the mountain and try to imagine what it used to be like.

Epilogue

Doing the research for this paper I discovered that there were many, many changes to the power system. Many more than I had thought. From an engineering and economic viewpoint, these changes were all expensive to accomplish and none of the equipment was ever used long enough to pay for itself. One should recognize that the electrical power industry of the 1890’s was like the computer industry of the 1990’s. The equipment, systems, and performance were being improved and changed on a daily basis. A system that was state-of-the-art one day was obsolete the next month. Along with his other expenditures in trying to complete the Alpine Division, and maintain a first class operation for his customers, Professor Lowe expended a large deal of money to make the power system work. All of this did not help his solvency.Ed. Note. My thanks go out to John who, when I suggested research on the subject of the Mt. Lowe Power systems, he jumped right in with both feet. John was the obvious man for the job. Watch for more on the subject through papers and lectures.

John P. Harrigan graduated from Cal Poly in 1970. He is a Licensed Electrical Engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power with 29 years service.

John is a member of the Scenic Mount Lowe Railway Historical Committee and a volunteer with the U.S. Forestry Service working on the preservation of the old Mt. Lowe Railway system.

John was recently published in the Spring 1998 Dogtown Territorial Quarterly with his LONE WOMAN OF SAN NICOLAS ISLAND.

Return to Echo Mtn. Echoes, Spring 1999 Cover

[ Issues | Search | Help | Subscribe | Comment | Websites ]

Send email to Echowebmaster@aaaim.com to report any problems.

Last modified: February 12, 1999

No part of this paper may be

reproduced in any form without written permission from:

Jake Brouwer

All articles and photos were provided by:

Land-Sea Discovery Group

Copyright © 1999